Research and Activities

Survey and Geophysical Prospection

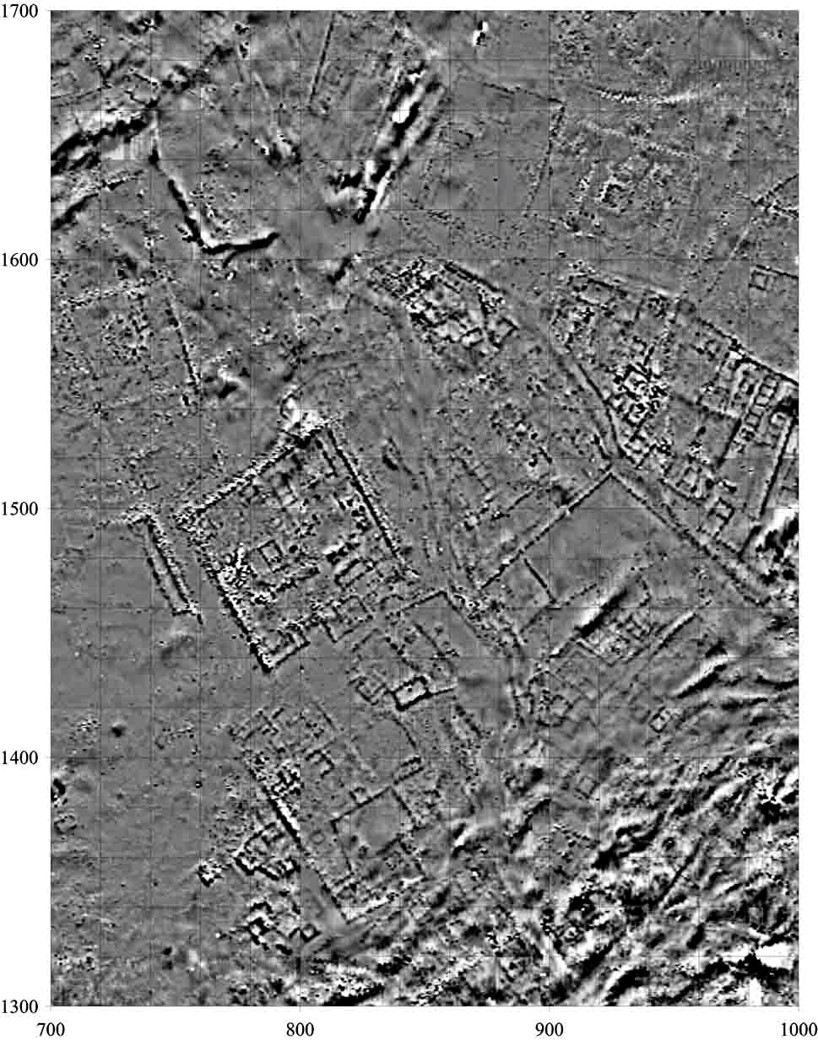

Magnetometric subsurface survey maps of the central lower town displays numerous urban compounds with internal structures and streets.

Systematic surveys of the urban landscape are especially important at Kerkenes, including an aerial photography survey of the entire site completed in 1995, a Global Positioning System (GPS) micro-topographic survey completed in 2000, the geomagnetic survey completed in 2002, and the ongoing geophysical prospection surveys. The eight-year geomagnetic survey revealed many of the buried walls, structures, and urban blocks across well over 90% of the 271 hectares of the city, with the data providing particularly good detail in areas where fires intensively burned the city during its destruction. This survey is more than sufficient to allow the reconstruction of a plan of the general internal structure of the city, beyond what was visible on the surface, other than in the remaining areas that lie buried beneath the later Byzantine castle, which covers a small area of the site.

Ongoing survey using an electric resistivity meter reveals better detail of buried walls and surfaces, particularly in areas where the fire was less intense during the destruction of the city. By combining of all four of the datasets the project is able to reconstruct a plan of the city and to investigate that plan through simulations, spatial analyses, and select excavation.

Excavations

Current excavations at Kerkenes are focused on understanding the people and households that lived within the city during the late Iron Age. To do this we have started major excavations within one of the urban blocks that define the city’s internal structure. These walled compounds contain a range of different building types and open areas, and we are using an analysis of these structures and the different activity areas that we encounter to identify different groups of people and their daily activities within the urban block. This evidence, together with the geophysical plan of the city, will allow us to begin to reconstruct the social organization of the city and compare the inhabitants of different urban blocks.

Previous excavation uncovered over 8,000 square meters of this enormous city. The earliest excavations were undertaken for a few weeks in 1928, long enough to place the city within the Iron Age. These brief excavations were followed by long-term excavations across the city since 1996. Major areas of excavation have included a portion of the city’s palatial complex as well as one of the seven city gates. These more recent excavations have greatly benefited from the presence of the geophysical surveys, the data from which allows us to precisely place trenches within the buried city in order to answer specific research questions. They’ve also benefited greatly from the presence of a wide range of project experts and specialists working with the excavated material in order to help answer these research questions.

Systematic excavations of residential contexts reveals important information about the household activities of the people who lived at Kerkenes 2600 years ago.

Environmental Archaeology

Environmental archaeology, the study of human relationships with environments in the past through the analysis of archaeological remains, includes the use of techniques from archaeobotany, zooarchaeology, and geoarchaeology. At Kerkenes, our program of analysis focuses on archaeobotany, although animal bones and geoarchaeological samples have been systematically recovered during recent excavation seasons. These data give special insight into the agricultural economy that supported the establishment and growth of the city. Archaeobotanical research at Kerkenes is being compared with extensive prior work on agriculture at Gordion to explore Phrygian agricultural adaptation to the dramatically different climatic regimes of these two cities.

Materials Analysis

The study of ancient materials and technologies provides important insights into the daily social and cultural lives of the people who lived at Kerkenes and their interregional interactions. Scientific analyses of archaeological artifacts uncovered and conserved at the site inform us about different types of materials like pottery, metals, or glass and how they were produced, traded, consumed, and ultimately discarded. Laboratory analyses at partner institutions include optical and scanning electron microscopy, XRF, XRD, FTIR, and stable isotope analyses. One particular focus is the development of in-field analytical methods to rapidly determine material structure and composition without invasive sampling.

This portion of our project is designed to directly intersect with similar work at archaeological sites in Turkey, including Gordion and Boğazköy, to reach broader conclusions about the Anatolian Iron Age and ancient cities more generally.

Noël Siver conserving a tin bronze plaque in preparation for illustration, analysis, and safe storage.

Ethnography

Ethnographic methods are applied at Kerkenes to accomplish three major interrelated goals. First, it aims at understanding the local perceptions, representations, and narratives of the past and the archaeological site. Traditional ethnographic methods of participant-observation and in-depth interviews are used to understand how the locals appropriate the site-as-a-place and its past. Secondly, the ethnographic research studies the impact of the archaeological project, the knowledge it produces, and the presence of mostly “foreign” archaeologists on the local people. This part particularly investigates how the archaeological knowledge and the site’s rising touristic attraction have triggered the locals to reflexively re-evaluate the significance of the place and the past. In addition to traditional fieldwork methods, digital ethnography is also used in this part of the project to understand how the local community represents their relationship with archaeology and the site, and their perception of “heritage” through the photography they upload and their discussions on social media.

The final aim is to assess the needs, the expectations, and the goals of the local community about the practice of archaeology and the protection of the site in order to develop a heritage management program with them. This part of the project aims at producing a community-based participatory archaeological research program. However, developing a community-based participatory archaeology requires that we first understand local peoples’ meaning systems, their conceptions of the site, and their own senses and values of the past and ‘heritage’. In order to accomplish all of these goals, we have actively incorporated ethnographic methods into our larger research program at Kerkenes.

Heritage Management

The preservation and presentation of the cultural heritage that we discover is a high priority for the project. While the immense fire that accompanied the destruction of the city in antiquity took a heavy toll on both buildings and objects, our project includes restoration architects and conservators as an important part of the team. Working within the limits of what is physically possible, these experts strive to reverse some of the damage caused by the flames and to help preserve and make accessible the important features and finds. We are aided in these efforts by the latest technologies before and after excavation to plan, document, and stabilize what we have discovered for future years to come. Finds from the ancient city are on exhibit in both the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara and in the Yozgat Museum. Visitors to the site can also see the remains of the city wall, gates, and buildings in various parts of this rugged and beautiful landscape. We are working to present these remains and the city’s landscape within their historical setting as well as their important place within local memory and social engagement. This ancient city is a living location of cultural heritage with both local and global importance.

Conservation and restoration of the Cappadocia Gate allows visitors to see what one of the seven city gates would have looked like around the time of the destruction of the city.

You must be logged in to post a comment.