UCF Biologist Records Highest-Ever Voltage By Electric Eel

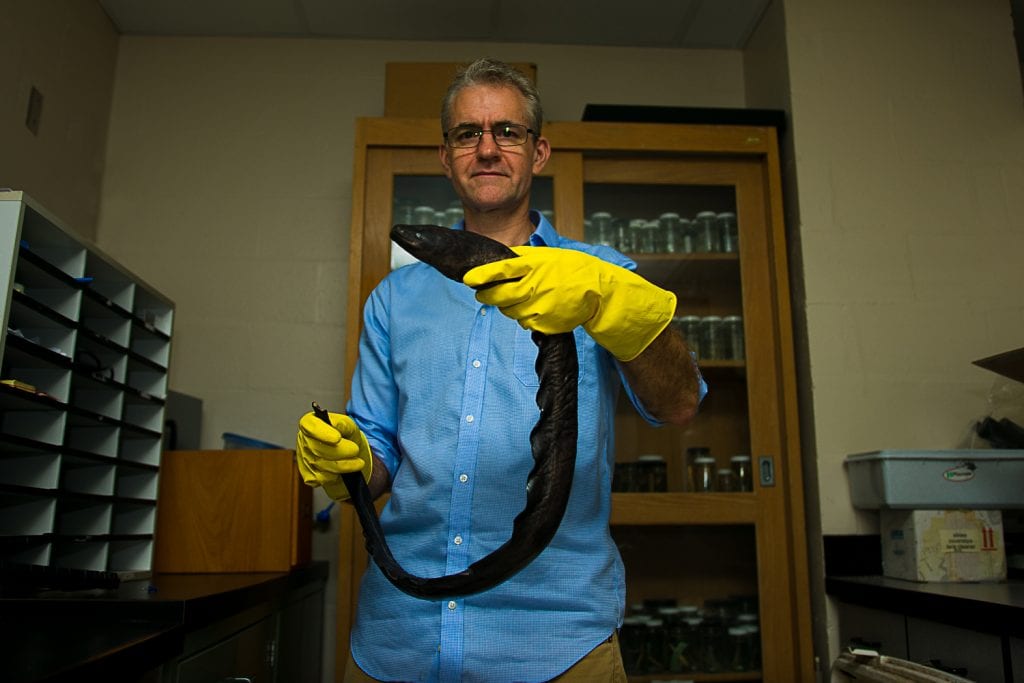

Dr. Will Crampton holds an eel captured in the Amazon.

A UCF biologist is attracting global attention for recording the highest-ever voltage generated by an electric eel — or any living creature, for that matter.

The record-shattering 860-volt eel was discovered by Associate Professor William Crampton, Ph.D., during an expedition to the Tapajós River of Brazil. The eel belongs to one of two new species described last week by an international team of scientists in the journal Nature Communications.

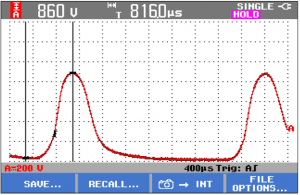

The record-breaking voltage measurement.

The eels are the first new species since Carl Linnaeus described the first, Electrophorus electricus, more than 250 years ago. The species with the new record voltage is named Electrophorus voltai after the Italian scientist Alessandro Volta, inventor of the electric battery.

“When I measured the Tapajós eel I immediately knew something was unusual,” says Crampton, an expert on electric fish and one of the lead authors on the Nature Communications paper.

The voltage of most home and business outlets today is 120 volts.

Dr. Will Crampton, Monster Fish host Zeb Hogan, and the team that helped capture the record-breaking eel. (Credit: Colm Whelan)

News of the discovery has spread well outside the science community to media outlets around the world. Shortly after the announcement, Crampton was contacted by the Guinness Book of World Records to confirm the record voltage. The previously reported maximum voltage was about 600 volts.

On Wednesday, Electrophorus voltai was officially recognized as both “most electric fish” and “most electric animal” by the organization.

Crampton’s record-breaking eel was unexpected. It began while filming an episode of National Geographic’s Monster Fish with host Zeb Hogan in 2014 when a photographer was shocked by a large eel that had emerged from a hole in the river bank. While shocks from electric eels are unpleasant, they’re not deadly. However, this one left the photographer pale and shaky.

The degree of the shock was a clue that the eels in this part of the Amazon jungle are different, and a test proved that suspicion. Crampton began the process of measuring the voltage by stretching out the fish on a non-conductive plastic tarp and placing electrodes on its tail and snout. These electrodes were connected to a voltage-measuring oscilloscope. Because electric eels are air-breathing fish, being out of the water for a few moments does not harm them.

Crampton speculates the unusually high voltage of Electrophorus voltai may be related to the low electrolyte content of the rivers it inhabits, but he says that’s for future research.

One of the biggest takeaways, Crampton says, is the discovery of the two new species after more than 250 years of scientific discovery and research in the Amazon.

“It’s a testament to how important it is to preserve the Amazon’s incredible biodiversity,” Crampton says. “We’re still in the pioneering phase of uncovering what’s out there.”