Purple Martin Project Teaches Field Work, Unlocks Biodiversity Mystery

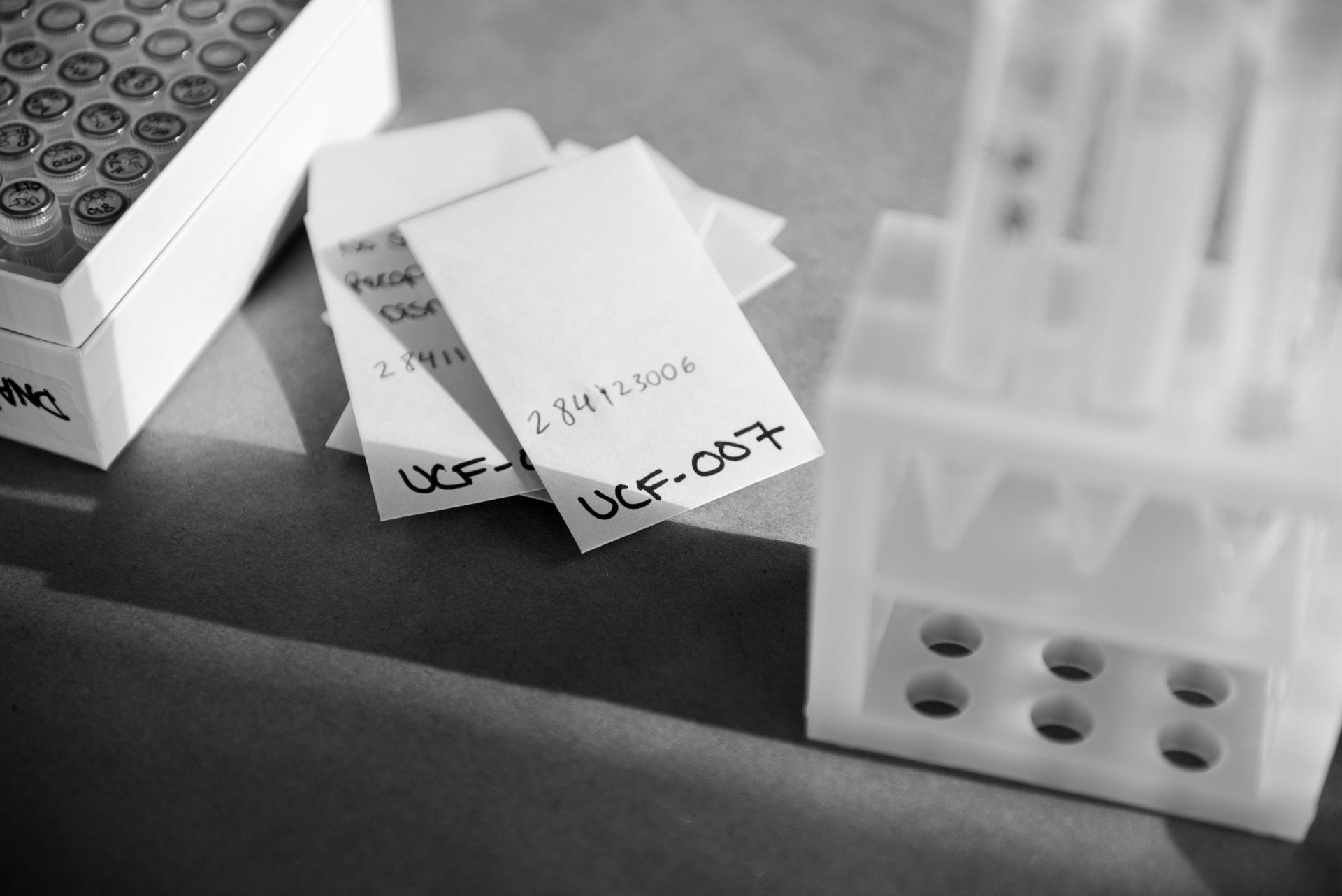

Anna Forsman accepts a tool during a recent field operation collecting samples and data from Purple Martins on UCF ‘s main campus.

A hands-on research project on UCF’s campus is teaching students field work fundamentals while unraveling the source of a major loss of bird biodiversity.

The project is led by Department of Biology Research Scientist Anna Forsman, Ph.D., and focuses specifically on the decline of Purple Martins.

“It’s important for us to study these birds from a biological standpoint so that we can figure out the causes of population decline and how we can further prevent it,” said Forsman, a member of UCF’s Genomics and Bioinformatics Cluster. Many of the students come from Forman’s ornithology course and are part of the Wild Symbioses Lab.

The 2021 phase of the project had 144 nesting gourds distributed across 12 sites on campus, with a total of 40 nesting pairs to study — up from 12 nesting pairs in 2020. This season, students learned how to band birds (both adults and nestlings) and how to take various morphometric measurements, including wing and tail length. Forsman anticipates expanding the program in the future to include studying behavior and migration.

The main studies underway in the Wild Symbioses Lab are: how ectoparasites influence adult and nestling health, and “fecal forensics” or determining what birds are eating and feeding their young by analyzing insect DNA from fecal samples.

According to Purple Martin Conservation Association, there is evidence that demonstrates die-offs or disappearances coincide with the local spraying of commonly used garden pesticides. Whether these incidents are caused by a lack of food or direct poisoning is unknown; the lab is also investigating how pesticides influence ectoparasite loads and, in turn, how both pesticides and ectoparasites influence Purple Martin health and reproductive success.

Forsman says from an educational standpoint she hopes that students both from her classes and outside the lab will gain an opportunity to learn more about these migratory birds. A recent field event both collected direct data from blood and other biological samples, as well as mounted trackers on the birds so scientists can track their migration.

“We get the chance to study these birds and interact with students and faculty that are just as interested in learning about Purple Martins,” Forsman said. “It’s a win-win all around.”