How UCF Research Is Changing the Way Scientists Track Animals

An assistant professor in the Department of Biology is reshaping how scientists understand animal movement, habitat use, and conservation needs through mathematically rigorous models.

Written by: Emily Dougherty | Published: February 2, 2026

Wildlife researchers today collect unprecedented amounts of animal movement data. From passerine birds outfitted with lightweight GPS backpacks to elephants collared with GPS devices as heavy as car batteries, location data have become central to conservation biology, ecology, and wildlife management.

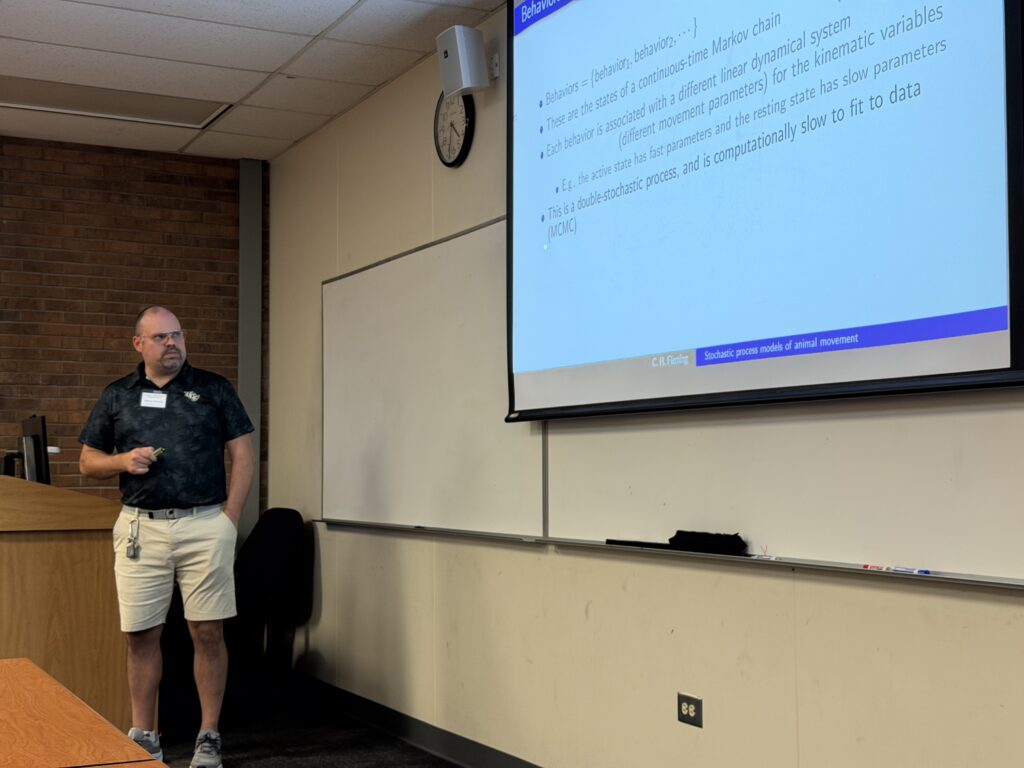

At the UCF Workshop on Mathematical Biology and Differential Equations, held Jan. 15–16, Christen Fleming, an assistant professor in the Department of Biology, discussed work at the crossroads of biology, mathematics and statistics aimed at making sense of these massive datasets. His research focuses on developing continuous-time stochastic process models that more accurately describe how animals move and how scientists should interpret that movement.

“There’s a lot of data on how animals move around and where they go,” Fleming says. “With this data, researchers want to answer questions about habitat use, population dynamics, connectivity, and even things such as vehicle collisions.”

In Fleming’s lab, doctoral student Nozomu Hirama is working on modeling changing movement behaviors, while doctoral student Erika Lin is working on applying these models to habitat corridor estimation. Additionally, Fleming shares that he is working closely with Dr. Zhisheng Shuai, a professor in the Department of Mathematics, on incorporating memory and cognition.

Why Traditional Models Fall Short

He addressed how many commonly used methods for analyzing animal locations rely on simplifying assumptions, particularly that each recorded location is independent of the last. While mathematically convenient, those assumptions often fail to reflect biological reality.

Fleming illustrated this problem using a case study of a black bear tracked near one of the Great Lakes. Conventional methods underestimated the area the bear actually used over time, missing much understanding of its future movements.

“The smaller estimate that assumes independence in the data is very much too small,” Fleming says. “It doesn’t capture the future locations of the bear 95 percent of the time.”

By contrast, Fleming’s stochastic process models account for the fact that animals move continuously and that successive locations are inherently related. These models also quantify uncertainty, which is an essential component for ecological decision-making.

Continuous-Time Models and Biological Meaning

Fleming’s approach relies on stochastic differential equations (SDEs), which model movement as a continuous process rather than a series of disconnected steps. This allows researchers to estimate biologically meaningful quantities such as speed, distance traveled and acceleration, which can be difficult or impossible to extract from simpler models.

“The parameters in these models are more biological,” Fleming says. “They’re not tied to the sampling schedule. They reflect how the animal actually moves.”

He says this distinction matters because animal tracking data is often irregular, collected at different time intervals across studies, species, and technologies. Continuous-time models allow comparisons across datasets without conflating biological behavior with technological limitations.

Choosing the Right Model Matters

Fleming and collaborators tested these models across more than 700 animal movement datasets. Their findings showed models that assume independence were supported by the data less than 1% of the time.

“Depending on the method you’re using, home-range estimates can be two times too small—or even 20 times too small,” Fleming says.

As GPS technology improves and data are collected more frequently, ignoring autocorrelation in movement data only worsens these errors. Fleming’s work demonstrates that model choice can dramatically alter scientific conclusions, especially in conservation contexts.

From Theory to Tools

Beyond theory, Fleming’s research emphasizes practical workflows for biologists. His approach involves fitting multiple candidate models, selecting the best one statistically, and then using it for model-based inference whether it’s to learn an animal’s home range or predicting future movement.

“We fit a bunch of models, select the best one, and then make an inference based on that model,” Fleming says. “That can have a very large impact on the results people get.”

The goal is to provide tools that are both mathematically sound and usable by researchers working in the field.

Looking Ahead: Nonstationary Movement and Behavior

Because animals do not always behave the same way, Fleming’s lab is now extending these models to account for nonstationary behavior such as daily activity cycles, seasonal changes, and behavioral switching between resting, foraging, and traveling.

“Animals go to sleep. They wake up. Their movement isn’t stationary,” Fleming says. “We need models that reflect that.”

By incorporating time-warping functions and behavioral state switching, Fleming says he aims to capture these complexities without sacrificing computational efficiency.

A Foundation for Future Conservation

Fleming’s work provides a mathematical framework for animal movement modeling which is grounded in the principle of maximum entropy and flexible enough to adapt as data quality improves.

“There’s a natural family of models that includes everything people are already using,” Fleming says. “And there’s a clear path to making them better.”

As conservation challenges grow more urgent, these models offer researchers crucial data to understand how animals move and how best to protect them.