More Sea Turtles Come to Florida, but Reasons are Mysterious

This year’s early count of sea turtles nesting on Florida beaches is encouraging, though there are many unknowns in the numbers.

Welcome to the mysterious world of sea turtles, which spend much of their life far from Florida’s beaches encountering fishing boats, oil spills, plastic trash and any number of other perils.

Nesting by loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles has been trending up in numbers for nearly the past five years along the state’s coast. But there have been significant dips and climbs in their nest counts.

Green turtles, for example, have wowed researchers with their growing preference for Florida beaches. Yet while last year’s nest count was surprisingly high, this year’s is down, which experts expected.

Named for the color of their fatty tissue, green turtles go about nesting in a peculiar way. Their nest counts predictably are up and down every other year.

“To me, it’s one of the great enigmas in sea-turtle biology,” Llewellyn Ehrhart, a pioneering turtle researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Central Florida. “It seems it would have something to do with food availability and nutrition, but I don’t know of anything in ocean biology that is so regularly scheduled high, low, high, low, year in and year out.”

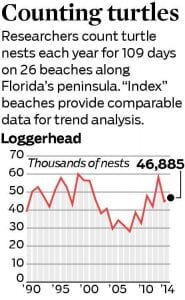

The turtle kings of Florida’s coastline, loggerheads, which have huge heads relative to their 3½-foot shells, deposited eggs in 46,885 nests this year.

That count was from the state’s “index” locations at 26 beaches, where nest monitoring has been done by researchers using the same methods since 1989.

Index counts are done during a 109-day window, which means tallies are smaller than annual totals, but the index data are valued for detecting trends.

“Every year, it’s always a little bit of a surprise for what we get,” said Anne Meylan, a senior research scientist at the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. “The biology of the animals is really complicated, and they live a long time, and they are affected by things far away.”

Since 2010, loggerhead nest counts at the index sites have amounted to a rebound. The count in 1998 of 59,918 plunged to 28,074 nests by 2007. By 2012, the nest count was back up to 58,172.

“We don’t know why they went down, and we don’t know why they are coming back,” Meylan said. “That makes us a little bit more cautious.”

Scientists are interested in whether sea turtles were killed in greater numbers through the early 2000s by commercial fishing, which then adopted measures to reduce turtle mortalities by the late 2000s.

Many scientists doubt the evidence supports that hypothesis, but there is much agreement the spike in loggerhead deaths was caused by problems or threats far from Florida.

Just what those threats are is what UCF scientist Kate Mansfield is trying to figure out by attaching miniature, costly trackers to young loggerheads.

“I’m especially interested in their early, developmental years,” Mansfield said. “There is very little known about what they do, and I think their behavior offshore may have some part in what we see in nesting.”

There is wide agreement that Florida and federal protections have contributed significantly to survival of sea turtles, especially green turtles, which were on the verge of disappearing from Florida in the 1970s.

“Once we got to 1978, restaurateurs had to get all the green-turtle steaks out of their freezers, and green-turtle soup disappeared from menus, and most people stopped killing them, and guess what, they came back,” Ehrhart said.

Laws protecting turtles and their nests have been accompanied by progressively better attitudes among communities in dimming their seashore lights. Green turtles, in particular, are spooked by artificial lighting, scientists say.

“That has sort of spilled over to Florida,” he said. “I don’t think anybody knows the reason for this. Between the time they hit the water as hatchlings and the time they come back 800- or 900-pound adults, there are hardly any records of them appearing anywhere.”

“It’s a real head-scratcher where leatherbacks are spending their growing-up years.”

To read original article click here.