UCF Anthropologist’s Research is Changing Lives

John Starbuck, Ph.D., thought studying anthropology might lead him to a career in a museum, but it’s done more than he could’ve imagined – his research and discoveries are changing the lives of people affected by Down syndrome and those with cleft lip or palate.

Growing up, Starbuck wasn’t interested in college. His mother worked minimum-wage jobs and his father wasn’t around. Despite his home life, he became a 21st Century scholar in eighth grade which gives disadvantaged children an opportunity to attend college as long as they meet the requirements of a good GPA and pledge not to commit crimes or use drugs. Starbuck also credits his interest in higher education to a girlfriend who helped motivate him. As an undergraduate he was accepted into the McNair Scholars program at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis.

“I bought into the idea that an undergraduate education could take me somewhere different and ran with it,” Starbuck said. “I worked in a lot of restaurants in high school, and it was easy to see that those paths have limited opportunities.”

As a McNair student, Starbuck was paired with a research mentor, Richard Ward, Ph.D., in his major – anthropology. It was then that he began studying facial reconstruction from a forensic context and completed a capstone project. This led him to Joan Richtsmeier’s, Ph.D., graduate lab in a highly ranked anthropology program at Pennsylvania State University where he became interested in Down syndrome and how an extra copy of a chromosome 21 alters facial development and appearance.

“We collected 3D images and when you go through them, if you didn’t know any better you would think they are all from the same family,” Starbuck said. “How do these individuals have different genetic backgrounds and all look so similar?”

His research led him to post-doctorate work at the Indiana University School of Dentistry in the Department of Orthodontics and Oral Facial Genetics looking at unilateral and bilateral cases of cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Traditionally, cleft lips and palates are repaired when the child is young by a plastic surgeon, but later can lead to dental issues, requiring additional surgeries. Starbuck realized they were forgetting something: everything in the skull is related – a concept known to anthropologists as morphological integration.

“In the skull, there were different issues that weren’t addressed because plastic surgeons tend to focus on making the soft-tissues of the face look right, but children born with clefts may have impaired breathing abilities due to internal, deep bony obstructions that make them more susceptible to infections,” Starbuck said.

By looking at 3D CBCT images of patient skulls, Starbuck and his plastic surgeon collaborators discovered that an extra bone obstructing the nasal airways needed to be removed to improve nasal breathing. These findings were published in the Annals of Plastic Surgery. His research gives medical professionals a chance to look at their work and look at patterns of differences, rather than single changes. Starbuck recently had another research breakthrough at a lab he partners with in Indianapolis run by Dr. Randall Roper, a geneticist.

Using EGCG, an extract from green tea, Roper’s team of researchers treated Down syndrome mouse models to see if EGCG toned down the over expression of a gene known as Dyrk1a, which plays a strong role in skull development. After six weeks, the offspring were measured by Starbuck and a student researcher, and they found that cranial vault shape was entirely corrected in Down syndrome mouse models treated with EGCG in utero. This is a major medical finding, published in Human Molecular Genetics. Starbuck and Roper, along with their collaborator Paul Territo at the Indiana University School of Medicine, want to look more in detail at the brains to see if they were also affected and are currently seeking funding to do so.

“The interesting thing is that most medical practitioners have given up on preventing health issues that occur due to trisomy 21, and focus more on treating what they can to improve quality of life,” Starbuck said. “But we need to do more research on the skull and brain to be sure, and funding is absolutely necessary to carry out these experiments.”

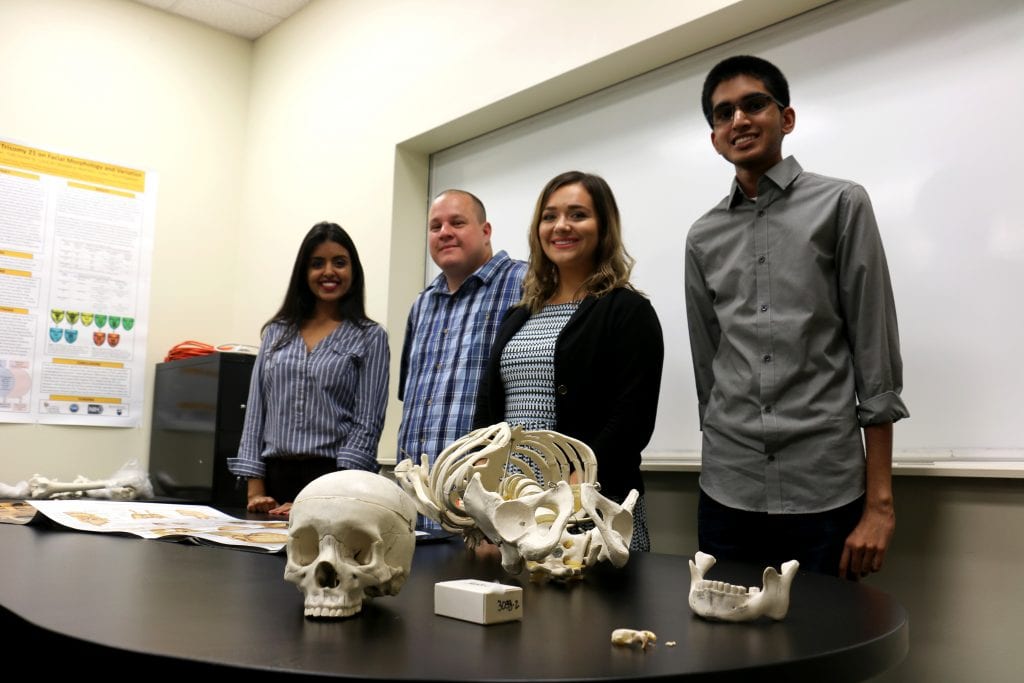

While Starbuck seeks more funding for that project, he works with students at UCF in his Image Analysis and Morphometrics Lab. The undergraduate student researchers are doing qualitative work recording CT and MRI scans of children with Down syndrome in collaboration with a local doctor. They are helping to create a database for future quantitative research.

Uma Ramoutar is a recent UCF graduate who double majored in anthropology and biology. She loves the crossover between her two favorite subjects.

“Dr. Starbuck’s research is so exciting because when you think of anthropology you think of the old antiquated definition of digging stuff up and it’s absolutely not just that,” Ramoutar said. “The actual definition is the study of humans. It’s helped me so much in my other classes to know how we became modern-day humans.”

Ramoutar graduated in May and took the MCAT over the summer. Without her experience at the lab, she doesn’t believe she would be as well-rounded. Yaser Ahmad, a biomedical science major, agrees. Although a sophomore, he knew the key to his undergraduate career was getting involved with research.

“When you learn anatomy, it’s textbook images – perfect examples. But here in the lab we get to see children a few months old to 15 year olds,” Ahmad said. “I’m getting more and more proficient in seeing where structures are in the skull. It’s diversifying my understanding of what I’m learning in class.”

Shelby Lucia is another student researcher who will graduate with an anthropology degree, but has her sights set on medical school.

“Anthropology is so broad it gives you a well-rounded perspective of humans and human life,” she said. “Just taking a pre-med class on its own wouldn’t give you that.”

These are some of the different skill sets anthropology can bring to students. While Starbuck will continue his work to study the cranial effects of Down syndrome, he is also teaching students the importance anthropology can make in their future careers. From critical thinking skills to human and cultural biological diversity, his students will have an advantage in any field.

“Anthropologists tend to have excellent research skills, interpretive analysis, and the ability to communicate effectively in written and oral contexts,” Starbuck said. “These skills are transferable to many careers in today’s job market, although employers do not always know that someone with anthropological training can fulfill their needs. As anthropologists, we have to go the extra mile to educate the public about the power of our field and the significant contributions we make on a regular basis to improve the world we live in.”